An Amazing Discovery: Laura Bridgman

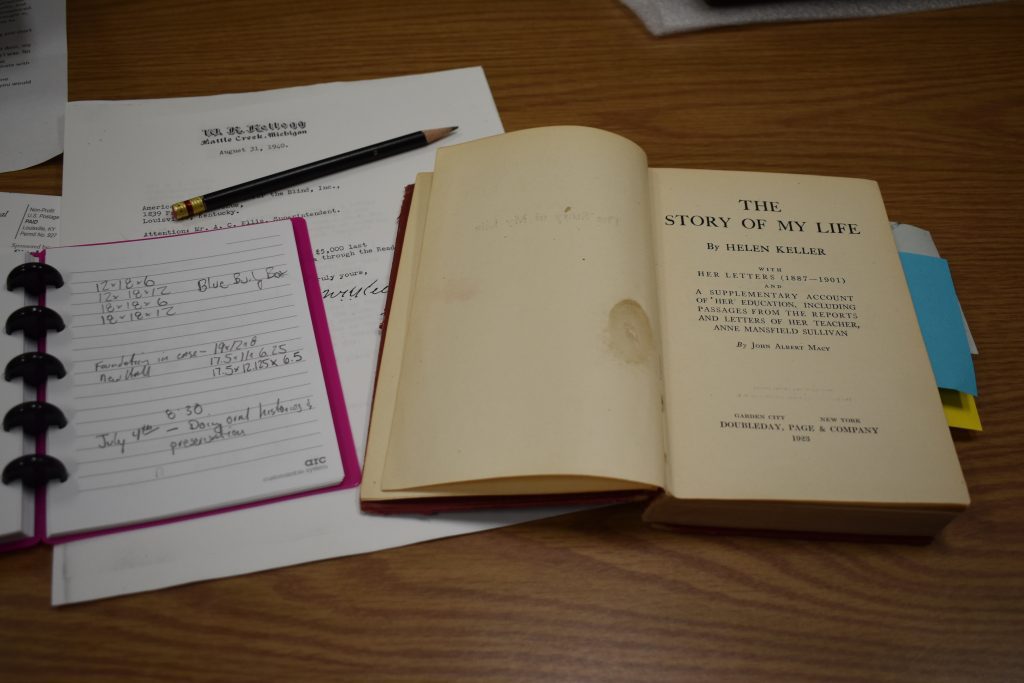

While working my way through a series in the American Foundation for the Blind collection called “Education, Rehab, and Welfare,” I found a set of folders with the subject “Outstanding Blind Persons.” Unlike most of the folders in the Archive, these did not contain unique correspondence or manuscripts. Each “Outstanding” folder was a collection of published articles on a specific person. The articles were by most standards modern. The work became routine for me until I encountered a folder for Laura Bridgman. I was excited at the thought that there might be some older, more unique articles in this folder. But I found even more than I had expected.

Laura Bridgman is generally acknowledged as the first deaf-blind child to successfully receive a formal education. Born in 1829, she was taught by Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe at the Perkins Institution in Boston. Her success became well known when Charles Dickens wrote of her in his book American Notes. It was that book that inspired Kate Keller to educate her daughter Helen through the Perkins Institution. Anne Sullivan knew Laura while at Perkins and used Laura’s educational experience as a guide when teaching Helen Keller. When Anne arrived at the Keller home, she even brought a doll for Helen that had clothes sewn by Laura Bridgman. Laura went on to correspond with Anne and Helen for the rest of her life.

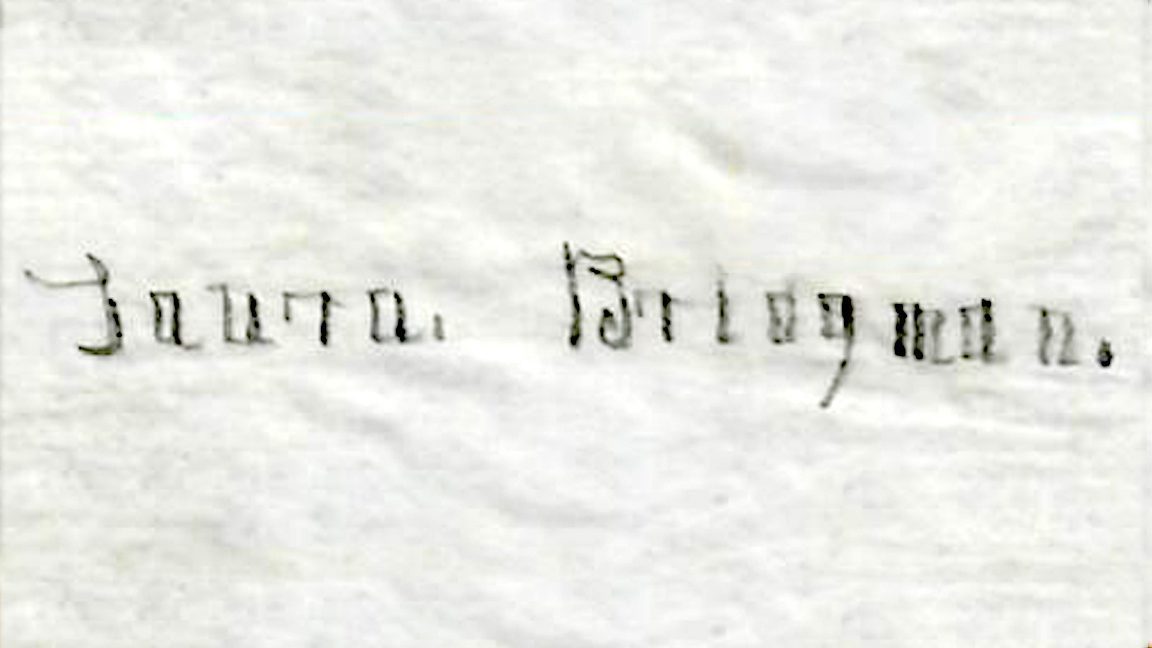

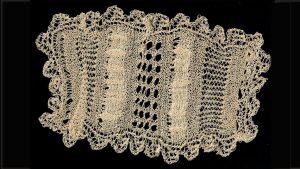

Inside the Laura Bridgman folder were three cut-down manila postage envelopes. Out of one, I pulled a card with Laura Bridgman’s handwritten signature on it. The second held a folded-up, three-page poem that had been handwritten by Laura in 1868. The third envelope had a sample of lace that had been knitted by Bridgman. Accompanying correspondence documented the donation of all of the items.

While every document may be an artifact, these items really stood out. They clearly took a significant amount of work and time in the hands of a legendary woman. And here was another physical connection to someone so important to the story, with connections to Dr. Howe, The Perkins Institution, Anne Sullivan, Helen Keller, and even Helen’s mother Kate. It was a find that required some reflection on my part. I really did have to catch my breath, because it was something I was not at all expecting when I began work that day. After immediately rehousing the items in archival sleeves, I contacted my counterpart at the Perkins Institution. Perkins does have several examples of poems and needlework digitized on their flickr page. The Perkins Institute was open to the public on Saturdays while Laura was there, and visitors often purchased lace or poems like this as souvenirs from Bridgman. But making this unexpected discovery was beyond exciting to me.

Justin Gardener is the AFB Helen Keller Archivist at APH.

Share this article.

Related articles

Finding Sadie

“The blind veterans here in the Helen Keller class are able, thru talking books, to obliterate the tedious hospital hours...

Thinking on Tasks Left Unattended

They say the best advice to young writers is to write about what you know. So rather than come up...

The Storied Life of a Time Capsule

Time capsules have long been an intriguing way for people to communicate through the ages, be they historians or grade...