How to Find the Silver Linings, Even in a Pandemic

After Meghan and Tyler Stott’s daughter, Kaitlin, was born in 2009 with albinism, she was fortunate to have the services of the Utah School for the Deaf and Blind’s Parent Infant Program nearby. But when the family moved to another state, they were told Kaitlin didn’t qualify for services, and when they later resettled in Washington, where they live now, they decided not to go through the frustration of seeking services again.

“We enjoyed our time at home together and I saw her visual impairment as a non-issue,” Meghan says. “She’s super-bright, so when we would go somewhere like the playground we would walk it together to find tripping hazards and then she would memorize it and was just fine.”

But when it was time for Kaitlin to begin kindergarten, everything changed — for both mother and daughter.

“We signed her up for kindergarten and I basically said, ‘Oh, by the way, she’s legally blind,’” Meghan says. When the school learned she wasn’t receiving any services, Kaitlin was paired with a Teacher of Students with Visual Impairments (TVI) who she’ll work with until she graduates.

Kaitlin also has an Orientation & Mobility (O&M) Specialist, and seeing the difference these services make completely changed Meghan’s mindset. “I went from ‘Oh, she doesn’t need services’ and ‘I don’t want her to be identified as the blind kid’ to ‘This is part of who she is and her blindness isn’t something for any of us to be ashamed about.’”

What’s more, seeing Kaitlin work with her teachers reminded her of the Parent Infant Program in Utah, where she had been fascinated by the TVI teaching and learning process. Three years later Meghan decided to go back to school. Today, she is a TVI at the Washington State School for the Blind. Meghan is in her second year of teaching and Kaitlin is now heading into sixth grade which means changing buildings from her familiar elementary school setting to a new middle school.

“I feel like I have the best job in the whole world,” Meghan says. “These kiddos have so much potential, and when you find what really hooks them to learn it’s incredibly rewarding to know you’ve made an impact.”

Bringing learning home

Meghan has the best of both worlds. Because she works part-time, she’s home when Kaitlin is — seeing her off to school and greeting her when she gets off the bus after school — and spends the rest of the day working with her 14 students.

“The students I work with are just amazing,” she says. “And I love the challenge because every day it’s something different — especially since the coronavirus started. I love the ability to be creative in our approach, no matter what’s happening.”

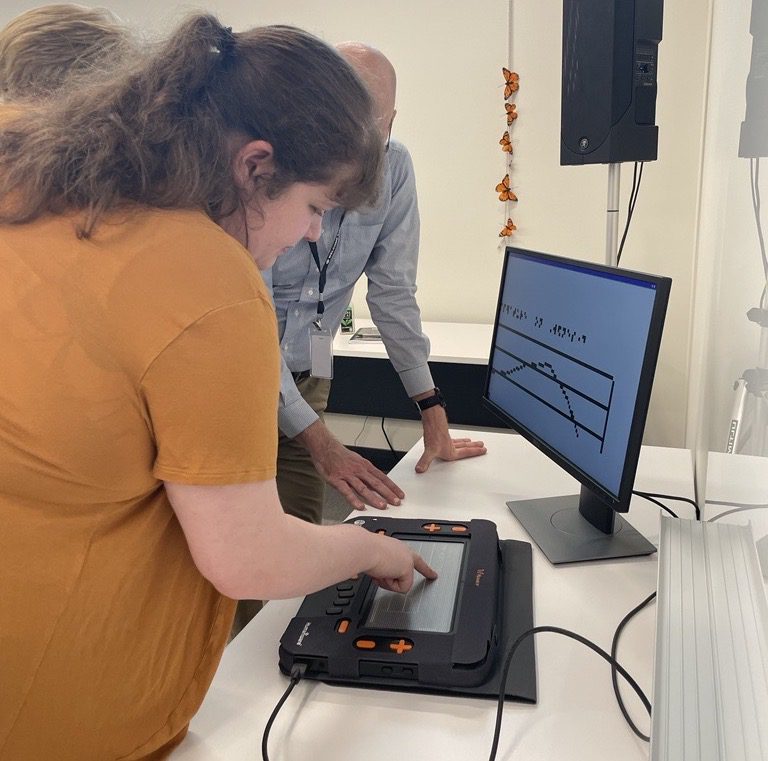

Meghan also admits it’s an advantage to have “a little test subject” at home. For example, Meghan was recently working with Kaitlin’s TVI to help her write an electronic document using her electronic braille display — and realized she could pass what she’d learned on to a student who needed to learn the same thing.

“Whatever Kaitlin learns is also knowledge I store, knowing I’m going to need it at some point,” Meghan says.

Being a mother of invention

With all of Washington’s schools closed, Meghan spends even more time with Kaitlin, and feels like the structure of each of their school days has made the transition easier. Like many people, Meghan looks for the bright spots that exist, even in the midst of a pandemic. One of them is that parents, including herself, can be more involved in their children’s Individualized Education Programs (IEPs).

“Sometimes I feel a disconnect between what we do at school and what happens at home, and there’s a tendency for parents to feel like they’re not a full member of the team,” she says. “But students are always with their parents more than they are with us, and ideally parents should be working on the skills we’re working on. Part of my job is to train them for that.”

Meghan relies heavily on videoconferencing with her students and their parents — and a lot of creativity. For example, she asks what items might be available around the house for them to work on their child’s IEP goals. In some ways, she says, it makes learning even more meaningful because the students are using real-world experiences to help them live independently in the future. For example, one student baked braille cookies and is learning how to garden.

Because of how quickly the schools closed, some students weren’t sent home with all the tools they needed, so Meghan has helped parents find them. In one case, she helped the mother of a child working on guided reach by mailing her a Joy Player from APH pre-loaded with sounds the boy enjoys. She’s also searched the APH catalogs to give parents suggestions and sent boxes filled with everyday items they can use to teach their children.

Discovering new educational approaches

In addition to online materials Meghan’s school district created to help parents teach their children at home, Meghan sends parents videos she records, offering suggestions on using various assistive technology or helping their children achieve their IEP goals.

For example, a couple of students have been resistant to using assistive technology because they don’t want other students to see them using it. For one student, Meghan and the rest of the IEP team encouraged them toward using speech-to-text while learning at home. Meghan hopes this student will recognize how much easier it is to use this tool so they will stick with it when they return to school.

She’s also optimistic that this experience might help teachers rethink some of their approaches. For example, Kaitlin had been struggling in science class because she had trouble reading the text, which was simply copied from the textbook and enlarged. But at home, Kaitlin has an online version of the book that’s much easier to read.

“I really worried at first about how our kids would learn from home, but now I’m really hopeful that at the end of this, teachers will realize there are different ways to do things,” Meghan says. “So many things would be more accessible in an online format — and there are companies out there making things accessible, so let’s use tools that are already out there.”

Share this article.

Related articles

Making Math More Accessible: Monarch’s Braille Editor and Graphing Calculator

Math is not the most accessible subject for students who are blind or have low vision. Adaptations to activities and...

Introduction to The Dot Experience

APH’s vision since 1858 is an accessible world, with opportunity for everyone. APH empowers people who are blind or low...

Adapted P.E. and SPORTS COURTS

We recently spoke with Amanda Dennis, Paralympic Goalball athlete and APH’s new Engagement Specialist, about the lack of adapted physical...