Susan Merwin’s Library

What would people know about you if the only clue to your identity came from the books you left behind? For myself, I gave away most of a very large library over the last five years as my family moved into a smaller house. So all I have on the shelf are the complete works of J.R.R. Tolkien, Thomas Carlyle’s “On Heroes,” Julius Caesar’s “Gallic Wars” (in Latin), a Bible, and Rick Atkinson’s marvelous Liberation Trilogy. There is probably a theme there for somebody to work with.

In 1923, the only woman to ever head the American Printing House for the Blind, Susan Merwin, died unexpectedly from influenza. Post-World War I was a bad time for the flu. Unfortunately, our collection contains very little of Merwin’s writing outside of a few published reports and we know more about Merwin from what she did than what she said or thought. As our assistant superintendent under B.B. Huntoon, she was a critical figure in introducing the new braille code adopted in the United States in 1918 as the “War of the Dots” was finally decided. Her testimony in front of Congress in 1919 was acknowledged by APH Board Treasurer Helm Bruce as instrumental in getting the federal quota fund increased for the first time since the Act to Promote the Education of the Blind was passed in 1879. She was a breath of fresh air at APH after forty-eight years of Benjamin Huntoon’s leadership. The building was painted and renovated. The school bought a lot of modern equipment. And she was a much beloved superintendent at the Kentucky School for the Blind (more on that in a future post, since we’ve discovered some interesting things there that help remind us all that 2023 is NOT 1923).

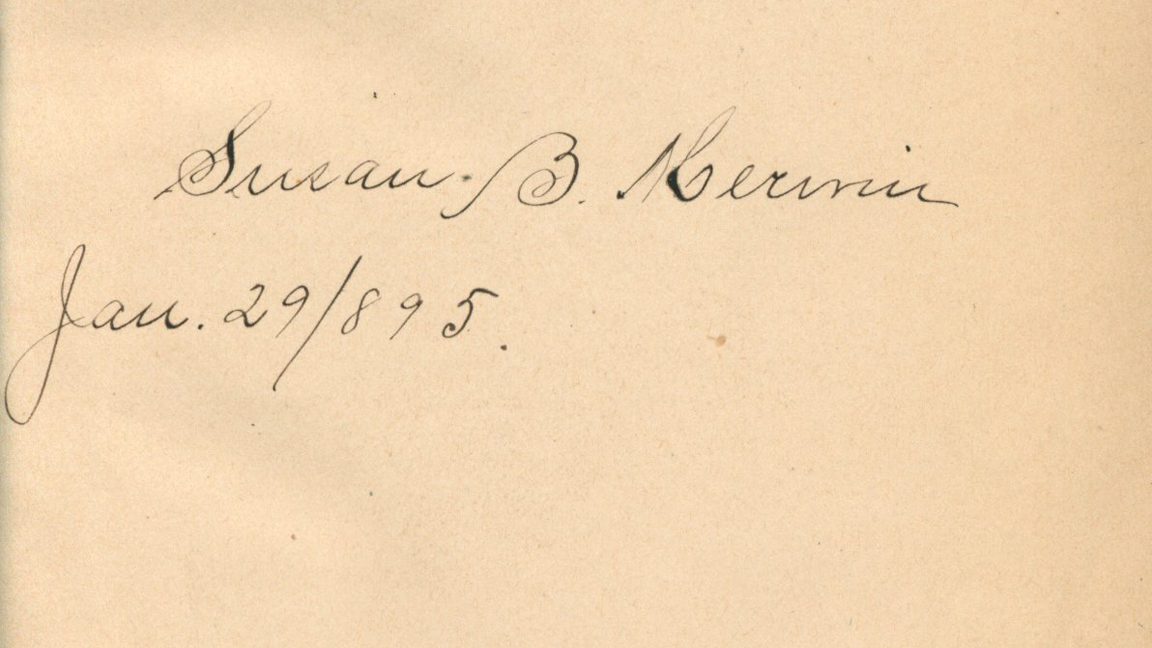

When she died, Merwin left her personal library to KSB. And don’t you know it, when the KSB Alumni Association partnered with us a few years ago to preserve their wonderful collection, our Collections Manager, Mary Beth Williams, started opening books on their shelves inked inside the cover with Susan Merwin’s signature or inscriptions written to her. That was exciting. Now, I thought, we can get a glint of Merwin’s personality, an insight into her thinking.

It is an interesting collection. There are only twelve books and let’s be honest, that’s a pretty slim slice of life to be making guesses about someone’s soul. Most of them are ordinary romantic novels of the day. I like to read that kind of stuff myself. Like watching a sit-com on television, sometimes you just don’t want to think too hard. For example, there is Clara Louis Burnham’s 1895 best seller, “Sweet Clover.” According to Google Books, “The novel follows the love story of the beautiful heroine Clover Bryant and Jack and the conflicts they overcome to be together. It is set during the 1893 great fair, made famous by the first Ferris Wheel, Cracker Jack, the first voice recording, and more.” Who doesn’t like Cracker Jack?

Then there is poetry, Thomas Moore’s exotic “Lalla Rookh,” a four-part epic piece about the fictional daughter of an Asian emperor which inspired a lot of nineteenth century music, theater, and visual art. We know Merwin loved literature and built an active theater program in her years at KSB with major productions and sumptuous costumes.

There is the biography of a man who lost his sight, Clarence Hawk’s 1915 “Hitting the Dark Trail: Starshine Through Thirty Years of Night.” The book is dedicated to writer and activist Helen Keller. Hawk was a naturalist, lecturer, and writer who knew Keller, lost his sight in an accident as a boy, and graduated from the Perkins School for the Blind. The book is his biography and its message can be summarized in his foreword, “To fight on when the battle seems lost, and to finally snatch victory from defeat, is the most sublime thing in human life.” That would have been a pretty typical message a young teacher might want to inspire her students with in 1915 America.

So the fact that the collection also contained a book by Teddy Roosevelt shouldn’t catch us by surprise. Roosevelt’s 1902 “The Strenuous Life: Essays and Addresses,” concentrates on what one reviewer called “having a strong work ethic, Christian fellowship, and the greatness of the American people.” Even if you have never read Roosevelt or studied his career, his cult of rugged individualism is a strong thread in our culture even today. It’s worth a second look. All of these books are. You can find them on the Internet Archive.

I don’t know that we know much more about Merwin, one of the great women of APH history. She loved to read, enjoyed a good story that transported her to faraway places, she valued pluck and courage in hardship, and she wanted her heroines to be beautiful and brave, and her students to learn the values held dear by other Americans. Did she think Teddy was a heck of a man? Or a blowhard? I’d bet on the former, but there are no margin notes, which is a shame.

And take a look at your own bookshelf. What would it tell a researcher about you and your times in 100 years?

Mike Hudson is the Museum Director of the Museum of the American Printing House of the Blind.

Share this article.

Related articles

A Message from APH President Craig Meador

A child who is blind or has vision loss is like any other child – eager to explore the world...