Blindness History Basics: The War on the Dots

Today, it is typical for individuals who are sighted to read print and for people who are blind or low vision to read braille. However, this wasn’t always the case. Instead of having one form of literacy, teachers of students who were blind or low vision in the 1800s and early 1900s used multiple systems to teach their pupils. A confusing and tumultuous time for the blind community, this 103-year conflict is known as the War on the Dots. Spanning from 1829-1932, many inventors and professionals competed during this time to create a single literacy system that worked for people who are blind or have low vision.

Some of the different methods used were…

Raised Letters

In 1784, Valentine Haüy founded the L’Institution Nationale des Jeunes Aveugles (Institute for Blind Youths), the first school for the blind in Paris, France. Two years later, Haüy invented the first raised letter book, Essay on Education for the Blind. Mike Hudson, The Dot Experience Curatorial and Content Lead said, “The raised letter books were the same print that sighted people were using, only they’re embossed, and the teachers were teaching the kids to trace those letters with their fingers and recognize them by shape. However, reading raised letter books was slow, and there was no way to write in this format.”

Braille

In 1821, Charles Barbier sent a dot code he invented to the school in Paris, where Louis Braille was a student. While it was the first method of reading and writing for the blind, each symbol in Barbier’s code used 12 dots with two columns of six dots, and it was slow to both read and write. The code was based on phonics, the way words are spoken, rather than the way words are spelled.

Louis Braille set out to correct the problems with the Barbier code, and by 1824, he had created the basic braille code we still use today. Unlike Barbier’s code, braille was made up of six dots with two columns of three dots and included a system for music and basic math. Braille published his invention in 1829. In the second edition of braille in 1837, Louis introduced the idea of contractions, where one symbol represented common letter combinations.

The braille system was formally adopted in France, two years after Louis died from tuberculosis in 1854.

Boston Line Letter

Samuel Gridley Howe, the first director of the New England Asylum for the Blind (now the Perkins School for the Blind), invented an angular, raised letter type called Boston Line Letter in 1835. “He tried to make a font that’s easier to read with your fingers” Mike said. “These characters that all kind of feel the same in a serif font feel different in Boston Line Letter.” In fact, the first books that APH printed in the 1860s were in Boston Line Letter.

New York Point

In 1868, William Bell Wait, Superintendent of the New York Institute for the Blind, introduced an adaptation of braille that he claimed had all the advantages of braille but none of its faults. He was primarily concerned about space, and his system was designed to reduce bulk. “Instead of being three dots high and two dots wide like braille, it was two dots high and of variable width depending on the letter you were writing,” Mike said. Originally called “Wait’s Point,” it became known as New York Point.

The Spread of Literacy Methods Across the World

In the late 1860s and through to the 1900s, these four codes were a hot topic, and teachers had to decide what system to teach their upcoming students. In 1871, the American Association of Instructors of the Blind (AAIB) adopted New York Point, and it was soon widely used in American residential schools for the blind. In the meantime, the British and Foreign Society for Improving Embossed Literature for the Blind published its Key to the Braille Alphabet and Music. It is based on the French braille code but is highly contracted. The British code was used in most other English-speaking countries. Joel Smith, a teacher at the Perkins Institution, complicated the debate further in 1878 when he introduced a second adaptation of braille called Modified American Braille, which was initially used by a few U.S. schools for the blind.

The Act Funds Free Textbooks from APH

In 1879, the U.S. Congress passed the Act to Promote the Education of the Blind. It created a fund providing tactile books from APH free of charge. Because free textbooks in New York Point were available from APH, most residential schools for the blind in the U.S. adopted New York Point.

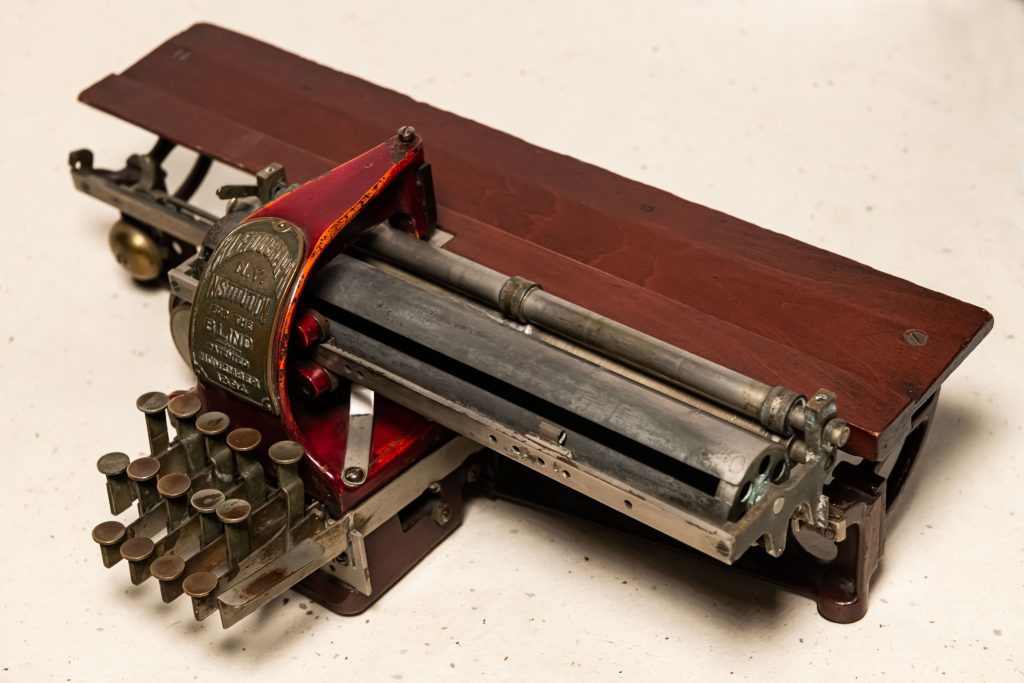

In 1890, Frank Hall, Superintendent of the Illinois School for the Blind, sought to invent a machine to write New York Point. Since the New York Point symbols are of variable width, the code is not ideal for mechanization. Instead, in 1892, Hall and a Jacksonville, IL mechanic named Gus Seiber invented the Hall Braille Writer, the first successful mechanical braille typewriter. In 1894, Hall invented stereotyping machines, allowing the inexpensive and rapid production of embossing plates. The plates allow a dramatic expansion in braille production over the next thirty years.

APH embossed its first textbooks in Modified American Braille in 1893. By 1905, the APH catalog contained books in raised letters, New York Point, and Modified American Braille.

Solving the Conflict

In 1905, the Uniform Type Committee was formed by the AAIB and the American Association of Workers for the Blind (AAWB) to adopt a single uniform code for all English-speaking readers. The committee decided that British braille—the original French alphabet code with a complicated set of contractions—was superior to both New York Point and Modified American Braille. Initially, the committee adapted a new code—Standard Dot—that combined the strengths of all three, but there was no enthusiasm for Standard Dot outside of the U.S.

A debate between braille and New York Point occurred in hearings in 1909 before the New York City Board of Education over what system would be used in the city’s day classes for students who are blind. The Board voted for braille, and at the next Annual Meeting of the American Printing House for the Blind, the board decided to split production between New York Point and Modified American Braille.

Having united the U.S. behind one code, the Uniform Type Committee negotiated with the British to unite the English-speaking world. In 1917, the Committee adopted Braille Grade One and a Half, which was British braille but with only 44 contractions. Unfortunately, British readers could easily read the American code, but American readers couldn’t read the British one. As such, the debate over braille wasn’t finished.

Finally, in 1932, at the London Type Conference, delegates from the English-speaking world approved a uniform braille system. Standard English Braille is the British braille code, but with a concession to the Americans: contractions do not break over syllables. Thus, the War on the Dots ended, creating a new age of braille literacy for people who are blind or low vision.

APH’s new museum, The Dot Experience, will bring braille history to life. All visitors will have a hands-on experience with pieces owned by Louis Braille, as well as other important pioneers and pieces of the braille revolution, such as the Hall Braille Writer.

Share this article.

Related articles

Blindness History Basics: History of Braille Writers

When fifteen-year-old Louis Braille presented his tactile system of raised dots in 1824, he hoped the new system would provide a...

Please Touch! Making Museum Collections Accessible

What do you think of when you hear the words “museum collection?” Artifacts like objects, paintings, photographs, rare books, or...

Connect the Dots

We are excited to announce our new family-based education series: Connect the Dots, powered by the PNC Foundation! Thanks to...