Exploring the History of the Monarch

Last year, APH and our partners released the Monarch, a 10-line display that renders braille and tactile graphics on the same surface. But did you know research on a full-page tactile display has been ongoing for over 40 years? Justin Gardner, the AFB Helen Keller Archivist, informed us that the AFB Archive includes three extensive files, as well as the original 1979 grant proposal related to this type of device. By delving into these documents, we can gain a better understanding of the obstacles our predecessors faced in bringing such a robust piece of technology into the world.

A Proposal and Prototype

In March 1978, Douglas Maure from the Engineering Department of the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) proposed the creation of a display with a minimum of a 50×50 pin matrix and a one-second refresh rate. Pins would be sized according to the Library of Congress standard, and no power would be needed to keep them raised. The display would also be self-contained, portable, and battery powered. Maure estimated the design and fabrication process to be nine months and cost a total of $28,000.

The National Science Foundation provided AFB with a generous research grant in April 1979 so they could begin work on what they now called the Transitory Electrically Alterable Graphic Braille Display (EAGBD). Soon, manufacturers produced a prototype with three cells and eighteen pins. They hoped the final display would be able to interface with many other electronic devices.

Improving the Design

Over the next two years, decisions about the makeup and target audience for the display shifted. The EAGBD went from utilizing pins to ball bearings and back to pins. However, it would have flat pins instead of rounded ones as the flat pins would be cheaper to manufacture. In June 1981, researchers found that the display might be useful for TVIs and students along with those in vocational settings, with tactile graphics being the biggest benefit.

Despite notes about how a single-line display would cut costs, AFB created another prototype with a 16×64 dot matrix. On November 11, 1982, the product was delivered to the National Science Foundation to fulfill their grant agreement, and a patent disclosure was filed.

Further Issues

In 1983, multiple problems kept the manufacturing process from moving forward. Tooling was estimated to cost one million dollars. A debate about whether cams or a direct drive would be better for the display ensued, and while the product, in theory, could be used by any PC with AFB software, the company didn’t know how graphics would be made and accessed on it. Prospective manufacturers also wanted multiple working models of the device, which was not cost-effective.

It was suggested that two types of displays be produced, a 40-character one for programmers and a full-page one for children learning to read. Team members worried too much collaboration would risk a loss of control and efficiency, and the resolution of the dots would limit tangible displays.

Final Documentation

Between 1983 and 1985, units with a 16×64 and 64×64 pin matrix were made. Unfortunately, all the models were expensive, noisy, slow, bulky, and unreliable. While a 1987 document stated that the design was finalized, a manufacturer was never found.

Like AFB, APH attempted to build a similar device. In 2017, we partnered with Orbit Research to create the Graphiti, a dynamic tactile touch display. Based on Tactuator™ technology developed by Orbit Research, Graphiti contained pins of variable heights to help represent maps and other graphical elements like grey shades and multiple color options. Graphiti was designed to be used in either a portrait or landscape orientation and connect to various electronic devices.

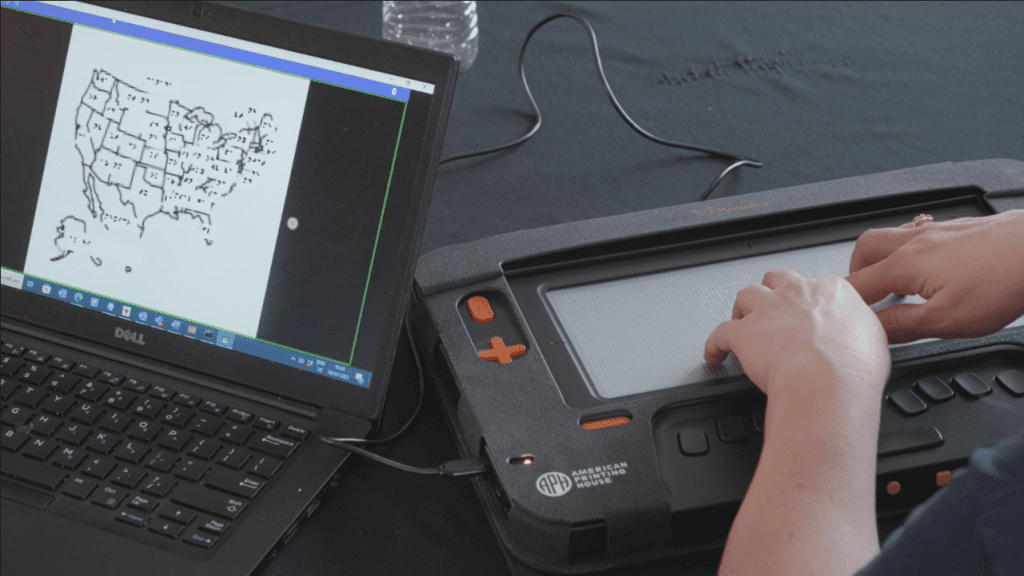

As time passed, APH wanted to create a display that would allow students to read both braille and tactile graphics on the same surface. It would be more advanced than the Graphiti, which was meant to display tactile graphics alongside a textbook. In 2022, APH and its partners began development on the Monarch, which was released in 2024. Now, students can electronically view braille and graphics together.

Check out our Meet Monarch page to learn about how this device is transforming the lives of its users.

Share this article.

Related articles

Exciting New Features for the Mantis Enhance Future Success

The Mantis Q40 has impacted the lives of numerous blind or low vision students and adults since its release in...

Increasing Electronic Possibilities: Connectivity on the Monarch

Technology bridges the gap between access and learning. Without screen readers on computers, applications like Google Chrome and Microsoft Word...

Setting a New File Standard with eBraille

Braille and tactile graphics allow students who are blind or low vision to learn the same educational concepts as their...