Hidden Legacies of Helen Keller

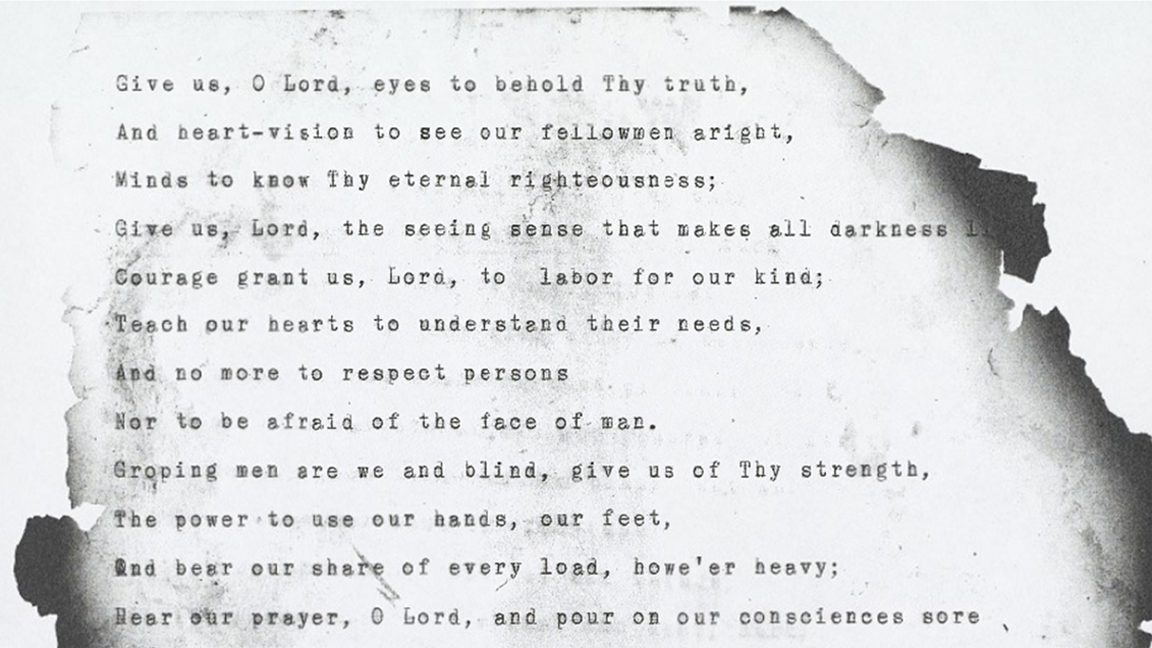

Burned manuscript recovered from the wreckage of Arcan Ridge, 1946. Photo AFB Helen Keller Archive

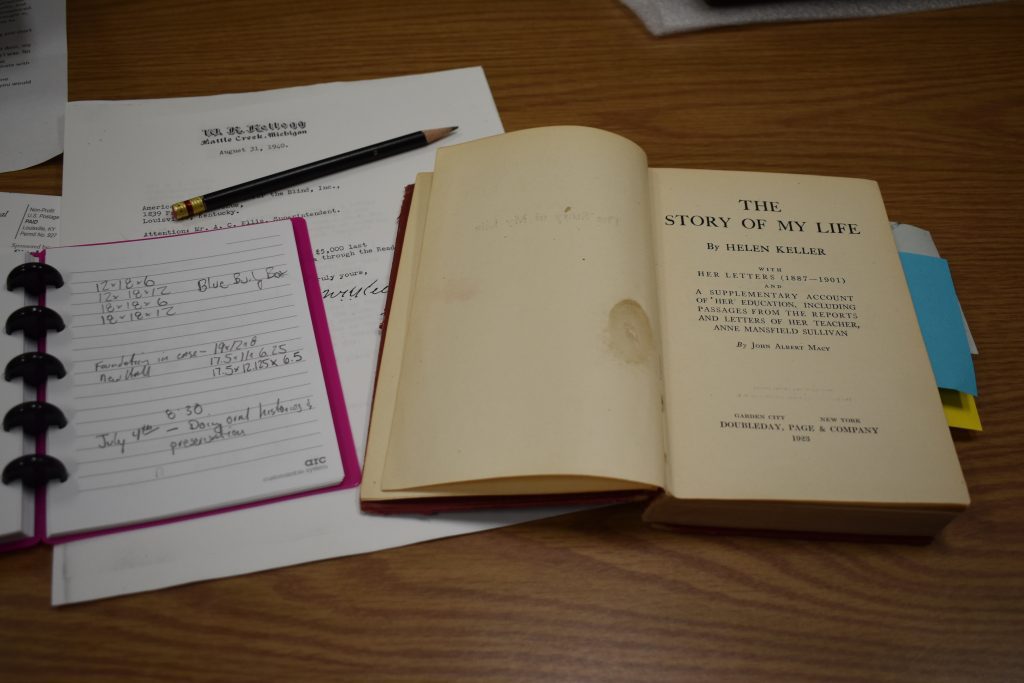

As we get ready to host our history symposium in September, Hidden Legacies of Helen Keller, at the Filson Historical Society, I’m planning what artifacts from the AFB Helen Keller Archive to set out. Right outside my office is the largest artifact in the Archive, Keller’s desk from her home in Connecticut. At least sometime this week and most every other, I come out and find someone there, lightly touching the top, head bowed.

This is what museums do best, arrange authentic encounters with real objects that real people used. And Helen Keller, despite what frivolous people post online, was a very real person. She and her assistant, Polly Thomson, were touring Europe in 1946, evaluating the damage done to blindness service agencies during WWII, when they learned that their house, Arcan Ridge, had burned to the ground.

The contents of the original house, including many treasures from her travels, were destroyed. Fire is the great leveler of history. It has no respect for kings or commoners or Kellers. The grounds were scattered with half burnt papers, drafts of Keller’s books and articles and letters. Her employer, the American Foundation for the Blind, arranged to have the house rebuilt. And the empty rooms had to be furnished. The desk itself is, perhaps, not all that interesting. It is walnut, with a raised lip to keep papers from falling off. It came from the Charles J. Lane Company, an office furniture supplier in New York City and cost $150.

And Keller wrote everything that came from her office between 1947 and 1968 right at that desk. If you are a fan of her work, a fan of her life, it is easy to become emotional as you stand before that piece of furniture she used so often. The symposium will share a few pieces from the Archive at the host site for the symposium, the Filson Historical Society, and we have more out beside the desk at APH. This symposium will feature presenters from across the range of disability and experience that will explore stories big and small that reveal how profoundly Helen Keller influenced the way we think and the way our world understands disability. Find out more and register. We hope you will join us!

Mike Hudson is the Director of the Museum of the American Printing House for the Blind.

Share this article.

Related articles

Finding Sadie

“The blind veterans here in the Helen Keller class are able, thru talking books, to obliterate the tedious hospital hours...

Thinking on Tasks Left Unattended

They say the best advice to young writers is to write about what you know. So rather than come up...

The Storied Life of a Time Capsule

Time capsules have long been an intriguing way for people to communicate through the ages, be they historians or grade...