National Poetry Month: An Interview with Susan Glass

In April 1996, the Academy of American Poets launched National Poetry Month, a time to celebrate poets’ role in our culture and remind readers that poetry matters. This year, we interviewed Susan Glass, a poet who is blind, about her literary journey and 2022 chapbook The Wild Language of Deer.

Meet Susan

Blind since birth, Susan Glass held a residency at the Cummington Community of the Arts in Massachusetts and earned her MFA from the University of Massachusetts/Amherst. Susan worked as an English professor at San Jose State University and West Valley Community College. Now retired, Susan co-edits The Blind Californian, a magazine for the California Council of the Blind.

In 2022, Susan released a new book of poetry, The Wild Language of Deer, which won the Elyse Wolf Prize offered by Slate Roof Press. Her poems have appeared in Snowy Egret, The Broad River Review, Birdland Journal, Fire and Rain: Ecopoetry of California, Honoring Nature: An Anthology of Authors and Artists Festival Writers, and elsewhere. Susan lives with her husband John and guide dog Omni.

Becoming a Poet

Susan said, “I have been writing poetry since childhood, and I think that what got me on that path was the natural world. I began listening before I could talk, and it affected my wish to connect sound and then realized that language was what helped humans connect sound. It helped connect humans to each other.” Additionally, Susan grew up listening to musicals including The Sound of Music and South Pacific. She said, “Before I could read, there were lyrics in my head. To this day, I compose melodically. A line will come to me and I’ll figure out how long I want it to be and where I want the rest to be.” Susan’s mother, an elementary school teacher, took great care picking out braille and audio books for Susan. Susan’s favorites are Winnie the Pooh and Now We Are Six by A. A. Milne along with Robert Louis Stevenson’s poem “A Child’s Garden of Verses.” Susan also read poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Frost as not many poetry books are available in braille. She said, “The beauty of braille is that it insists that you slow down and take your life a gulp at a time, a minute at a time, a line at a time, a breath at a time.”

The Wild Language of Deer

In 2016, Susan submitted her poetry to the Slate Roof Press Poetry Chapbook Contest/Elyse Wolf Prize. Winners of this contest are awarded $500, a three-year membership to the press, and the publication of their chapbook. Susan’s manuscript consists of poems surrounding the themes of family, nature, mythology, and how language connects those three things. The drafting process involved selecting poetry she had written, composing new poems, and cutting her work down again. Susan said, “I had no idea when I would sit down each morning that I was writing my book. I was just writing poems. Only when the book started to have this shape and be guided by others at Slate Roof Press did I have the ability to figure out what could go in and what could be taken out.”

The Wild Language of Deer is a 20-poem, hand-sewn chapbook with special die-cut binding and tactile features. A deer head gazes out at the reader from the book cover. This circular cutout is made of smooth paper interspersed with little bumps and dots. “The Wild Language of Deer” is spelled out in Grade 1 mega dot braille on the opening page of the book. Each cell is a hoofprint of a deer. “There’s a fold out braille copy of the poem ‘The Cellist Brings Me Autumn’ so you can fold it out and read the print copy on the left and the braille copy on the right. This is in the book so that people who could see could appreciate what braille looks like,” said Susan. At the back of the book, there’s an explanation of how braille works complete with a print alphabet of braille cells and contractions. There are also tactile woodcut illustrations of birds and deer throughout the book.

Susan’s Writing Process

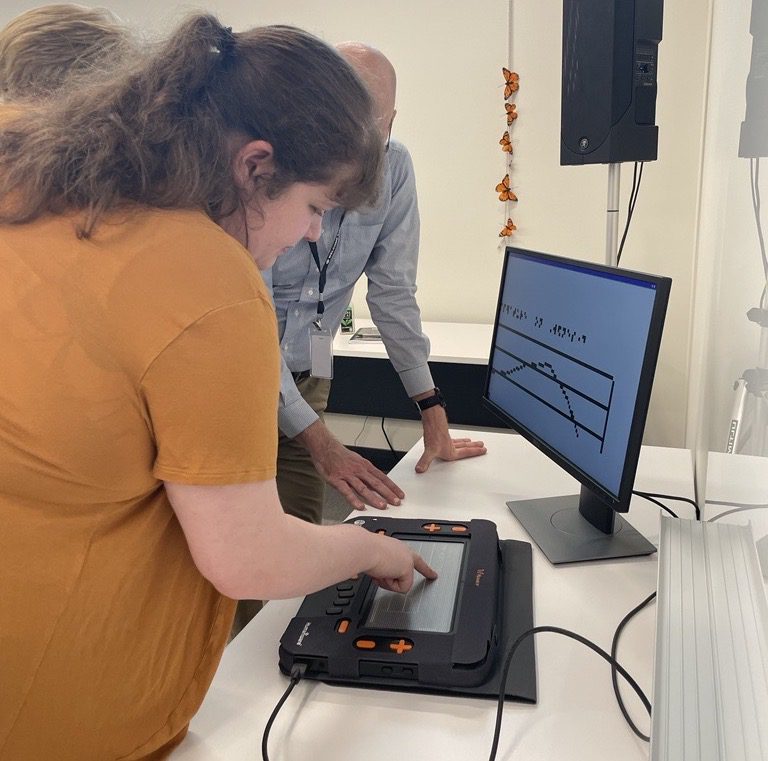

Susan draws inspiration for her poetry from an emotion she’s feeling, a sensory impression, an experience or memory, or a question she has. She composes her poems on a braille display. “When I am writing, I hear a line fully formed in my head and I write it down,” said Susan. “I work a line at a time, but it’s not disjointed because one thought in one line is leading to another line. I tell people when they read my poems to let the line guide them but also let the breath guide them.” Each poem in the chapbook tells a story and has melodic lines that end on strong verbs.

Susan described her revision process by comparing it to gardening. She said, “I plant everything under the sun and then I prune. It means there’s going to be a lot of language that goes away, but I don’t mind. It’s what I need to do to get where I’m going.”

Susan’s book contains poetry about blindness to match the braille aesthetics in the print copy. “Letter to Visual Cortex” is about Susan’s first memories of learning to read braille. Research has shown that the visual cortex, which is wired to the eyes of people who use their vision to read, will rewire itself to the fingertips for a braille reader. “I didn’t know anything about a visual cortex when I was six years old, but I do remember the sensation of connecting a word with what my hands were doing,” said Susan.

“I hope readers of my book will not be afraid of poetry,” said Susan. “I hope my book will make people enjoy it for what it’s supposed to be, which is an appreciation of the world and a re-experiencing of it through the senses.” Overall, Susan wants her poetry to make people happy, cause them to share it with others, and inspire readers to work to save the planet. She said, “I think we need to write about beauty because we have to see beauty so that we’ll fight to preserve it.”

Visit the Slate Roof Press website to purchase The Wild Language of Deer in print or audio today.

Share this article.

Related articles

Celebrating Global Accessibility Awareness Day with APH’s Danielle Burton

Celebrated annually on the third Thursday of May, Global Accessibility Awareness Day (GAAD) recognizes digital access and inclusion for those...

Making Math More Accessible: Monarch’s Braille Editor and Graphing Calculator

Math is not the most accessible subject for students who are blind or have low vision. Adaptations to activities and...

Introduction to The Dot Experience

APH’s vision since 1858 is an accessible world, with opportunity for everyone. APH empowers people who are blind or low...