Stevie Wonder’s Trail to Braille

This is part of our series on the importance of braille literacy. We asked braille readers about their introduction to the braille system and how braille has changed their lives. Find tools and resources to support braille literacy in our toolkit blog.

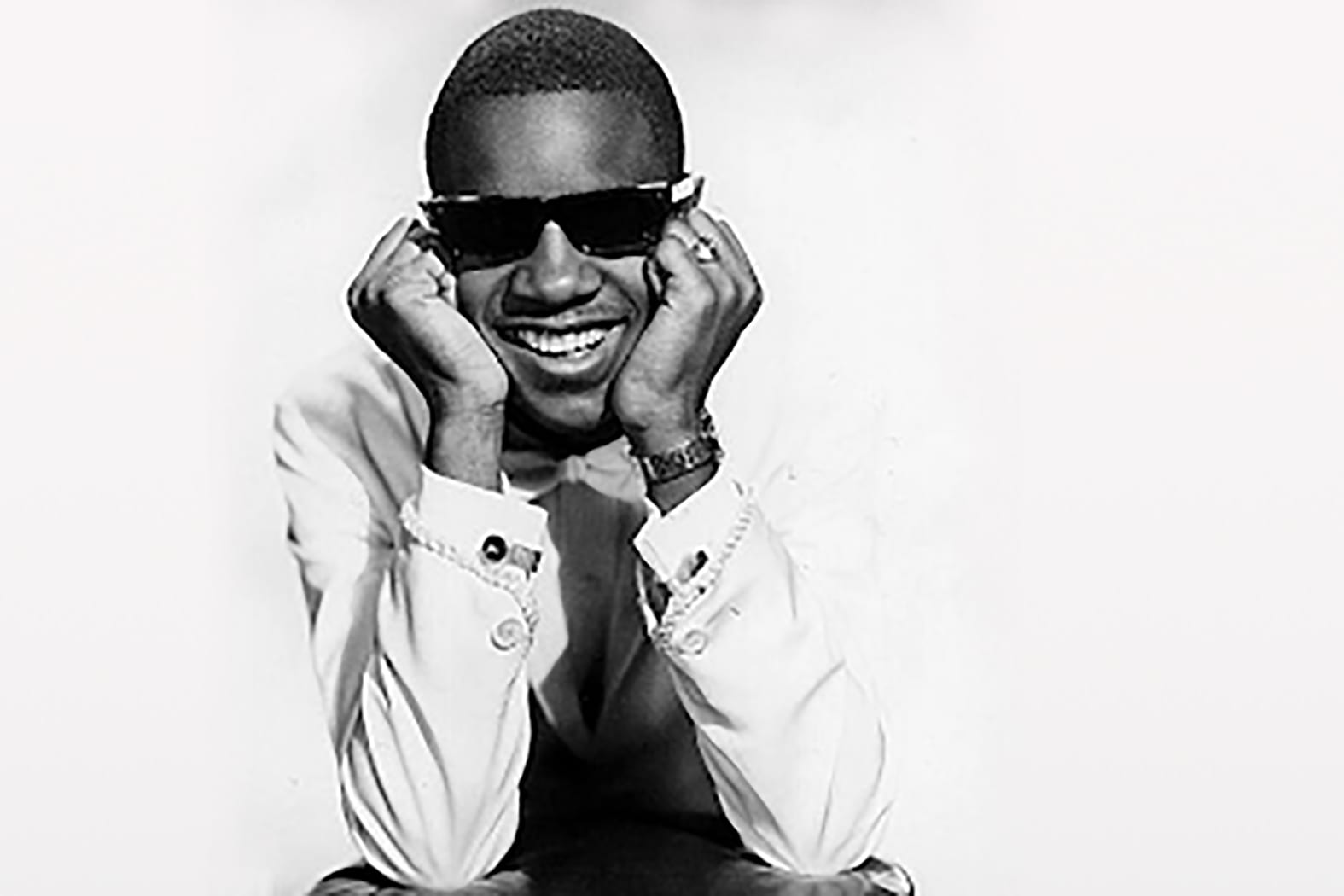

If you watched Stevie Wonder’s turn as an awards presenter at the 2016 Grammy Awards, you know he made a splash by reading the winner off an envelope embossed in braille, and Wonder took the opportunity to reaffirm himself as one of the world’s foremost advocates for accessibility.

But it wasn’t always that easy.

The little boy who would grow up to be Stevie Wonder was born Steveland Morris in Saginaw, Michigan in May 1950. Born premature, he was hustled into an incubator in the hospital’s nursery ward. Doctors knew the incubators provided vital warmth and oxygen and dramatically improved an infant’s chance at survival, but what they did not know was that too much oxygen could damage the baby’s eyes. And Steveland would be one of many thousands who would emerge from the experience blind.

Traditionally, kids who were blind had attended residential schools, but by the mid-20th century, larger cities had created day school programs. By that time living in Detroit, with his mother Lula and five brothers and sisters, Stevie attended Fitzgerald Elementary, the public school that hosted students with visual impairments. But he had attendance problems. Even as a boy of twelve, Stevie had been discovered by the hitmakers at Motown Records, and he, and his mother, were in trouble with the Detroit Public School System, for truancy.

Berry Gordy, the legendary head at Motown, tried to head off the problem by hiring a tutor, a middle-aged retired teacher from the Kentucky School for the Blind, Peggy Traub. Mrs. Traub didn’t mind tutoring the boy but found the job of supervising a teenage boy on a musical tour more than she could handle. She suggested contacting the Michigan School for the Blind’s well-regarded superintendent, Robert Thompson, to see if Thompson could recommend anyone. And indeed, Thompson could.

Ted Hull, a graduate of Thompson’s school, had just left Michigan State University with his degree as a teacher of the visually impaired. Contacted by Gordy’s sister, Esther, Hull agreed to take on the job. His story is told in fascinating detail in his 2000 memoir The Wonder Years.

It was 1963 when Ted met Stevie for the first time. Ted Hull found that although Stevie was technically a sixth grader, he had missed so much time that he would need to start Stevie out at the fifth-grade level. And he needed equipment: braille textbooks, a talking book phonograph, a tape recorder, a Perkins braille writer, a braille slate and stylus, braille paper, and a cubarithm board, a tool used to work out arithmetic problems in braille. And he needed to develop relationships, relationships with the tour coordinators and relationships at the Michigan School for the Blind, where Stevie would be enrolled as an ordinary student when not traveling the world as a superstar.

Classes had to be fitted in between recording sessions, rehearsals, and performances. Impromptu classes took place in hallways or corners backstage. As Hull remembered, “The world became his classroom.” And Stevie’s bright young mind absorbed it all like a sponge. It was a unique experience, one designed expressly for a very unique young man. In 1969, Stevie graduated from MSB. But his braille trail, his record as an advocate for full accessibility, was only just beginning.

What’s your braille trail?

Share your story to braille literacy with us for a chance to be featured in our braille literacy series: communications@aph.org

Share this article.

Related articles

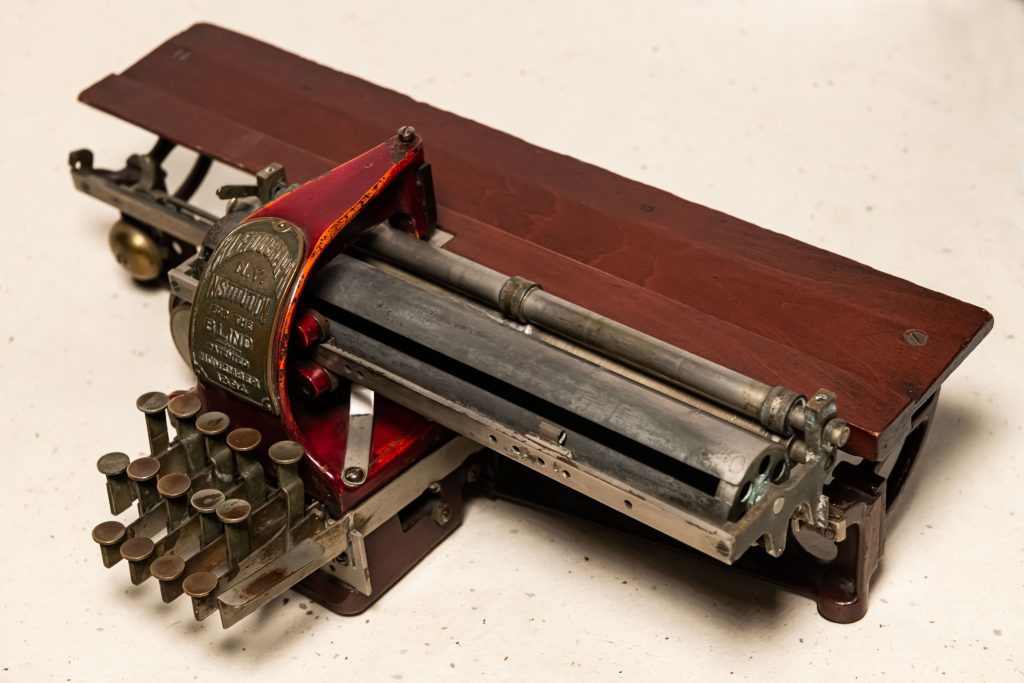

Blindness History Basics: History of Braille Writers

When fifteen-year-old Louis Braille presented his tactile system of raised dots in 1824, he hoped the new system would provide a...

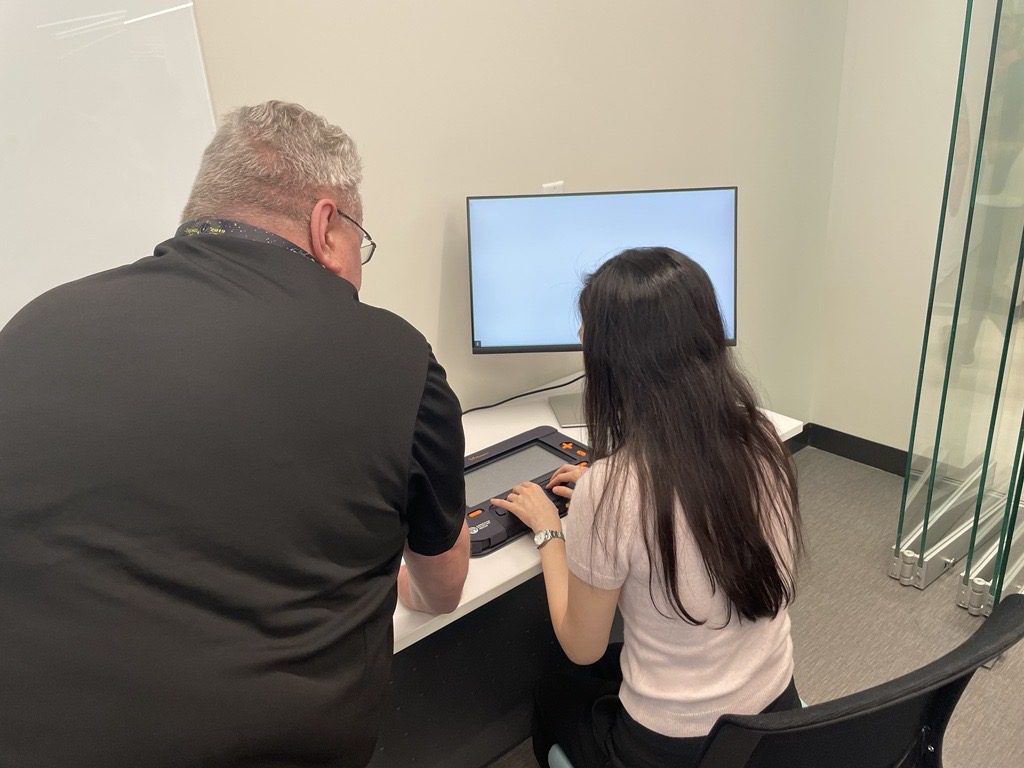

Simplifying Standardized Tests with the Monarch

Standardized tests can be a source of anxiety for students who are blind or have low vision. Although they are...

Setting a New File Standard with eBraille

Braille and tactile graphics allow students who are blind or low vision to learn the same educational concepts as their...