The Unsung Story of Nelle Edwards

It turns out blogging is not as easy as it appears. Not only do you need something fresh to say, but you also need fresh ways of saying it. My drafts all start out the same way. “I was researching this and I stumbled onto that, and it was pretty interesting.”

My family and my friends laugh when they hear a story like that because they think my job as Director/Curator here in the Museum of the American Printing House for the Blind is pretty cush. They think I spend my days researching what I want, writing about what I want, and sharing those stories with our visitors. And mostly that’s right—but we don’t have to tell everybody, do we?

So, with apologies, last week I was cataloging a book on the braille music code by a woman named Mary De Garmo from 1971. In the introduction, Mary De Garmo thanks a woman here at APH who I had never heard of, Nelle Edwards. It turns out that Nelle Edwards was the head stereotypist and primary music transcriptionist at APH in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. She is mentioned in the oral history interviews of a number of now-retired braille translators who started at APH in that period. But she is otherwise forgotten today. Nelle was one of two American delegates sent to Paris, France in July 1954 to a conference sponsored by UNESCO. The International Music Conference hoped to approve standard braille music notation for the entire world.

Nelle Edwards was the secretary of the subcommittee on music notation of the Joint Uniform Braille Committee, a body that would later become what we now call the Braille Authority of North America. She was one of the few true experts on the braille music code in the U.S. She was born in South Carolina in 1908, married Louisville florist “Lum” Edwards in 1939, sang soprano in the choir at the Walnut Street Baptist Church, and had a very talkative parakeet. We have thousands of photographs of our building, and our machinery, and our workers, but that we know of, we have not a single picture of this incredible woman. She retired for good in 1978, and was, no doubt at all, impossible to replace. I know all of that now, after a few days of research. Memory is so fragile. Nelle’s anonymity got me thinking about women’s history in general.

In the history of the blindness field, the history of education and rehabilitation for people that are blind and visually impaired, the early histories are flush with tales of notable men. Valentin Haüy, Francois Leseur, Louis Braille, John Alston, Johann Wilhelm Klein, Samuel Gridley Howe, Julius Friedlander, William Wait, Joel Scott, Oskar Picht, and Frank Hall. And as aware as I am, I have probably given a million tours where I didn’t mention the contributions of a single female character.

Women have, from the start, played an integral role in the education and rehabilitation of people who are visually impaired. Unlike the military, or industry, or hiking with Daniel Boone through the Cumberland Gap, two vocations that have almost always been deemed as appropriate for women were those of teaching and nursing. With their association with childrearing, it was almost always “OK” with society for a woman to pursue a career there. For most of the last 250 years, over which the blindness field emerged, the majority of people working in our field have been women, like Nelle Edwards. They maybe didn’t always get the credit they deserved or the promotions, but unlike fields like law, medicine, business, or the military, they didn’t have to justify their aspirations. Women like Nelle Edwards, who make their mark, deserve better from historians.

Share this article.

Related articles

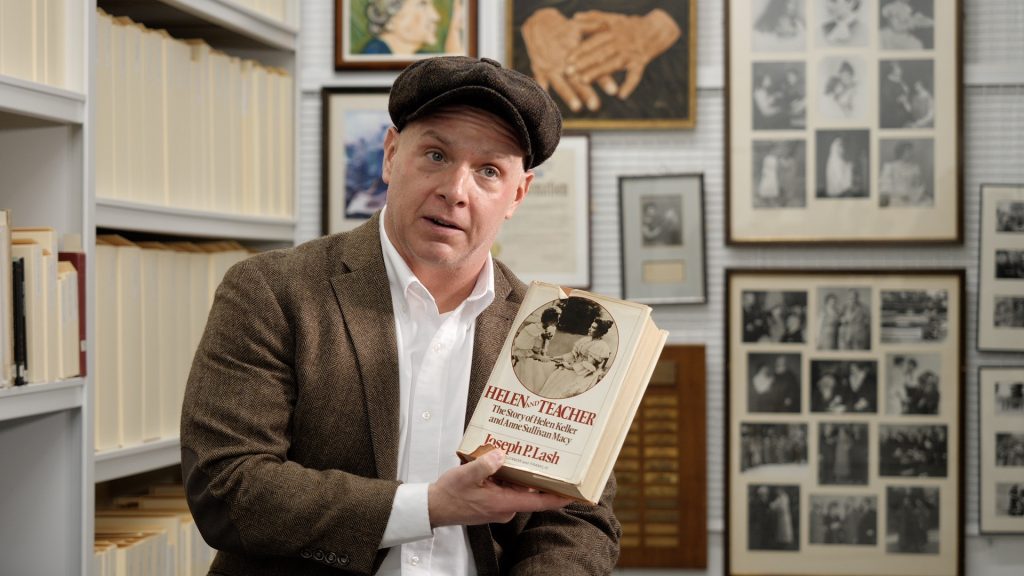

Unveiling a Legacy: The Helen Keller Time Capsule

Around the corner from the heart of braille production and product storage, sits a room tucked against the back wall...

Of Beautiful Springtimes and Unfortunate Transcriptions

Yes, it is good to be home now with the daffodils and hyacinths, the lawn thick with soft young blades...

Technological Relevance in an Ever-changing World

Everything old is new again. Or so the adage goes. But there is an underlying truth to it, even if...