The Wacky World of Flexible Records

If you’re old enough to remember begging your mom to buy breakfast cereal so that you could get the phonograph record printed on the back of the box, then you’re old enough to remember the wacky world of flexible records. I remember cutting a Bobby Sherman 45 off a box of Sugar Crisps and thinking how cool it was. The song was “In Seattle.”

For a time during their heyday in the 1960s and 70s, flexible records were seemingly everywhere and yet nowhere, and by that I mean for most people they remained a novelty. The Beatles put out a Christmas record every year for their fan clubs. Mcdonald’s issued a record with their latest jingle misrecorded. One version would win a big prize. They were basically tricking you into listening to their advertising. Computer magazines even tucked audio into their issues in the form of something called “audio software.” I have no idea how that worked.

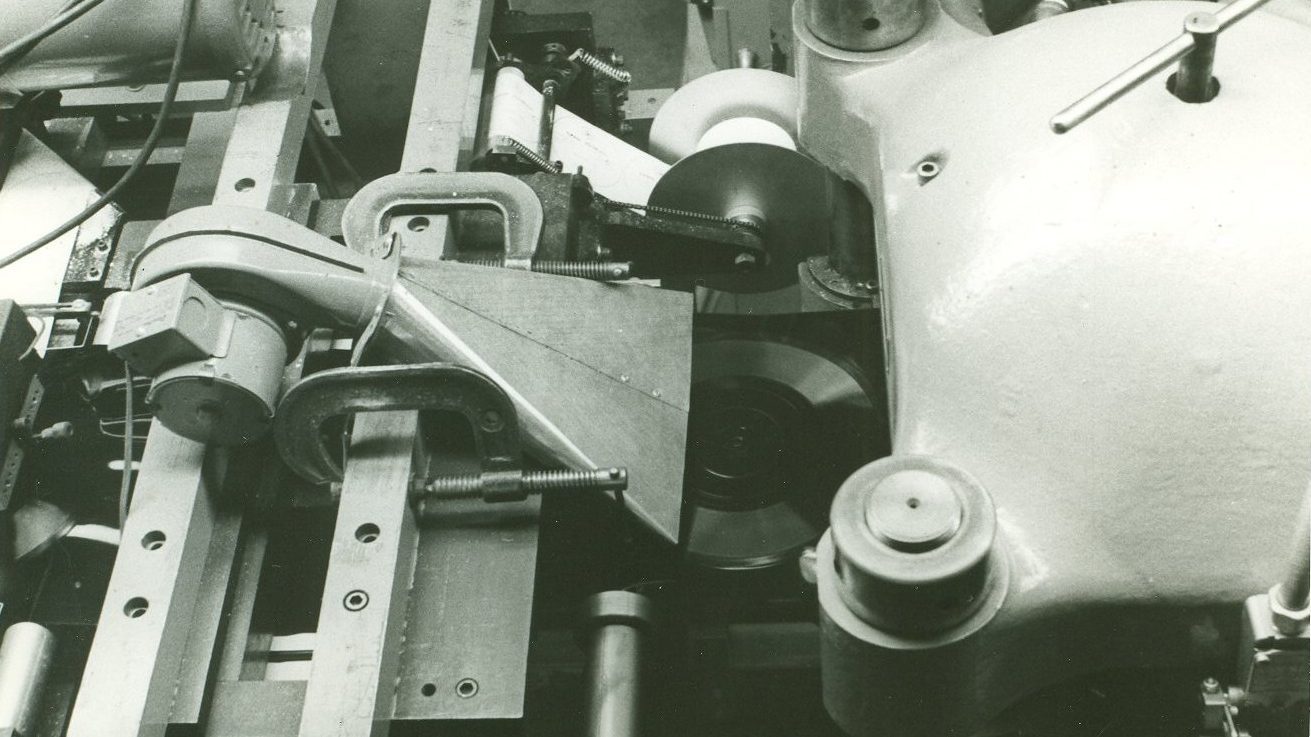

And in the midst of all this craziness, the American Printing House for the Blind got into the business too. The company had started recording and pressing rigid vinyl audio books in the 1930s. The process was complicated and expensive. For publications that consumers typically read once and discarded, like magazines, it was not very efficient. Flexible records offered a great alternative: easy to mail, cheap to manufacture. The manufacturing line was installed in 1972 and was quickly adapted to make issues of popular Talking Book magazines like Newsweek, Reader’s Digest, Ebony, and Sports Illustrated. We took on contract jobs for corporations like Sears & Roebuck to produce their annual reports on flexible records.

Flexible records were played on a phonograph. They weren’t meant to last very long, but we still have dozens and dozens in our museum collection which play just fine, but the sound quality isn’t the best. Hey, you get what you pay for. I’m told that sometimes you had to put a quarter or a steel washer on them to get them to play right. Eva-tone was the big national company that specialized in the format, and we have a few Talking Book titles—anyone remember Stephen King’s Firestarter?—produced for the Library of Congress by Eva-Tone. At APH, however, it was only used for magazines and the like.

At the same time, APH was introducing flexible records, however, we were also experimenting with audio cassettes. And gradually, cassettes increased in popularity and all phonograph records went into decline. APH produced its last rigid vinyl record in 1987 and discontinued flexible records in the 1990s. Eva-Tone went bankrupt in 2000, and the day of flexible records was over. Do you have a flexible record memory?

Micheal Hudson is the Director of the Museum of the American Printing House for the Blind.

Share this article.

Related articles

APH Behind the Scenes: The Talking Book Studio

Have you ever wondered how talking books are produced for people who are blind and have low vision? We spoke...