Our First Book

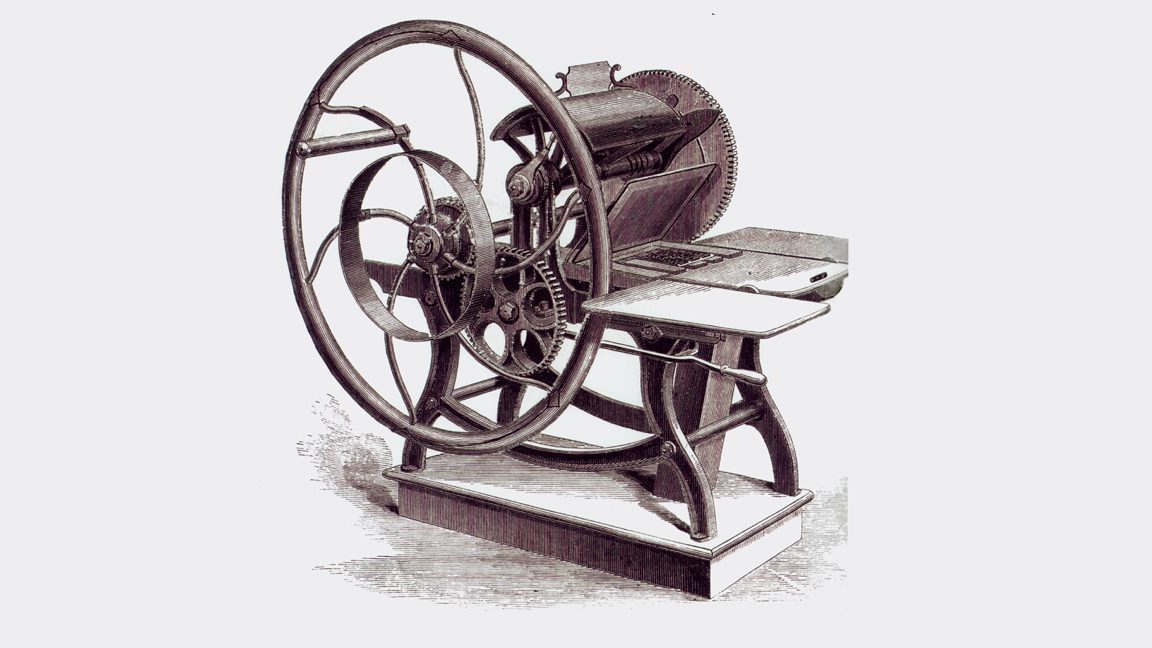

You’re not going to believe this, but with centuries of potential titles to choose from, all three of the first books from APH were essentially the same book. (OK, some may quibble.) For the record, APH bought its first press in 1863, from noted printing press designer and Boston raised letter pioneer Stephen Ruggles. And the early publications on that press were experimental, as Bryce Patton, our first superintendent, basically taught himself a very complicated process with which he had no experience. Sometime in 1867, according to the company’s second annual report, dated December 31, “the Institution has commenced the work of printing in raised letters for the Blind. A Book of Fables and Stories for Children has been printed…”

There you go. The first book title was A Book of Fables and Stories for Children, 1866. Unfortunately, we don’t have a copy of that first experimental book. In the report dated December 31, 1869, however, the APH Board bemoans the lack of a standard type font for embossed books—there were several but we won’t go into that here—and reveals it had stopped printing while the issue was considered. In late 1869, with no answer in sight, APH embossed “an edition of four hundred copies of Gay’s Fables…” Our museum has a copy of Gay’s Fables, a version of the works of John Gay, which first appeared in print in 1727.

Now come on! You’re telling me the first two books from the APH press were both books of fables? Ah, dear reader but it gets better. In the company’s fourth annual report, dated February 7, 1871, the Board announced “The work of printing, which was discontinued at the end of the year 1869, was not resumed until the 15th day of November 1870. Since that time we have printed four hundred copies of Fables for Children…” Thanks to researcher Taylor Hare from the University of Pennsylvania, we now know a copy of Fables for Children is preserved in the British Library in London, part of a collection of thirty-five embossed books collected by the library from an American bookseller in 1874.

So I wondered, why were fables written at a child’s level deemed so important to our company that, although there were extremely few accessible books available, we devoted so much early press time to their production? The written reports do not go into the logic behind the choices, as if it were too obvious to mention. But I found this by Robin Loftin at Remembering History, “Fables contain educational value that is often overlooked and underappreciated in our high-tech, modern world. Yet their value is matchless. Although some were written centuries (if not millennia) ago, the lessons on morality endure.” For our founders, it was not math, or science, or American literature, or geography, it was wisdom that mattered more than any other endeavor. And as a foundation for education, I guess I can get behind that.

Micheal Hudson is the Director of the Museum of the American Printing House for the Blind.

Share this article.

Related articles

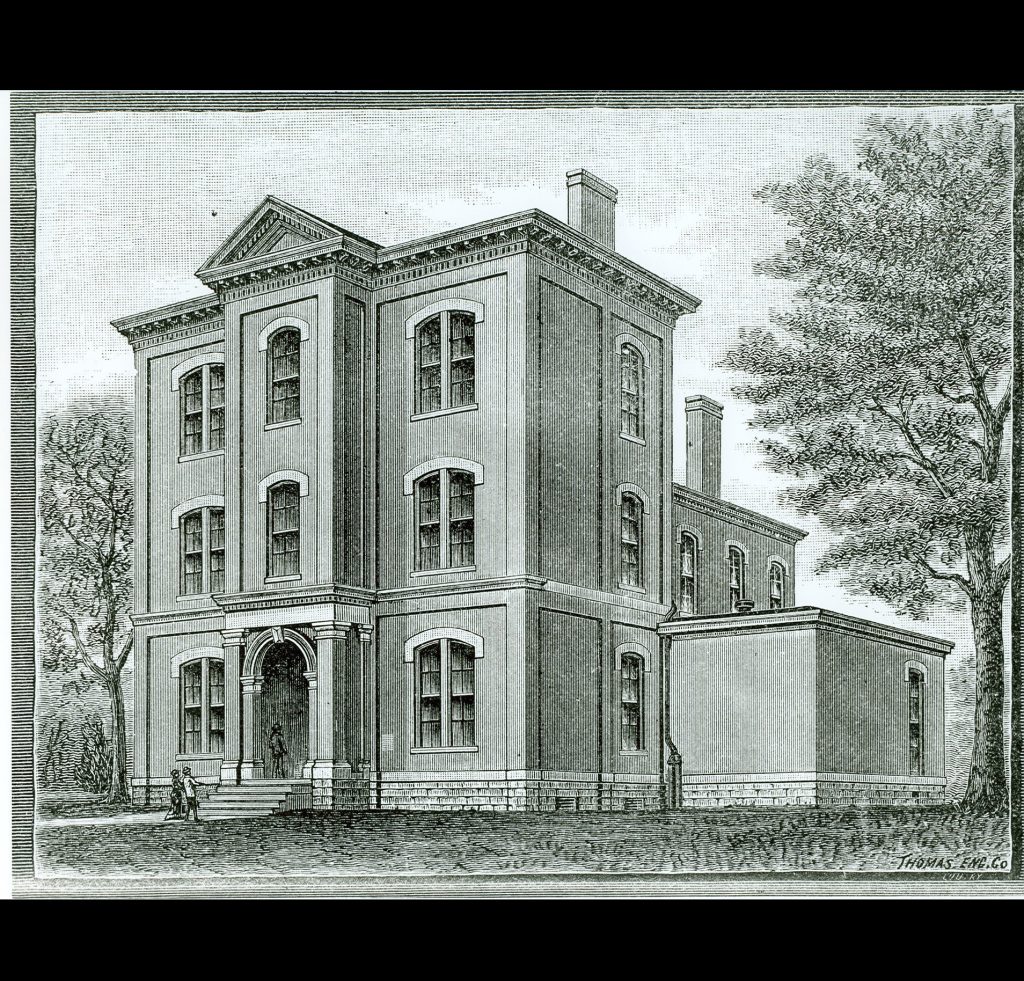

Celebrating APH Founders Day

On this day in 1858, the Commonwealth of Kentucky chartered the American Printing House for the Blind, recognized as a...

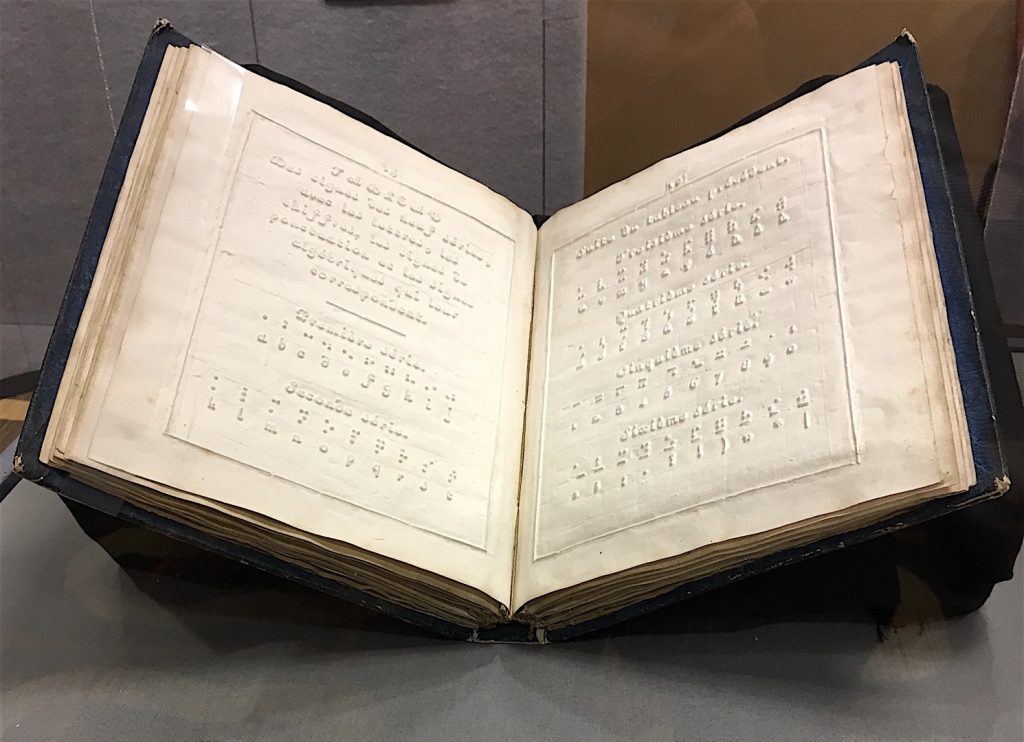

Blindness History Basics: The First Publication of the Braille Code

Louis Braille’s code lives on today as individuals who are blind and have low vision use his system to read...

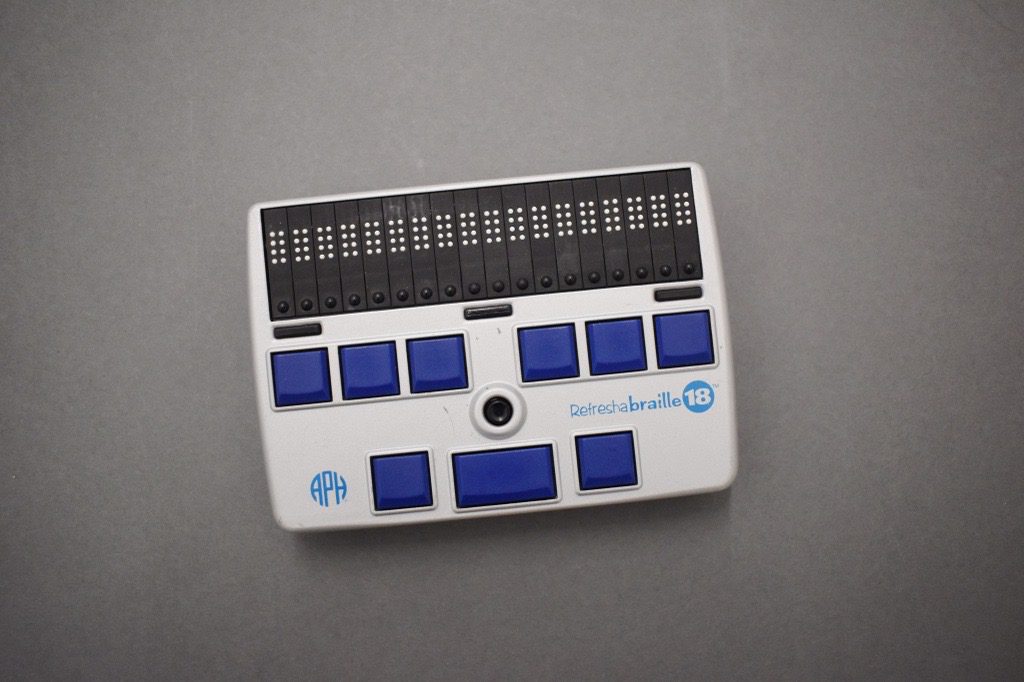

Blindness History Basics: A Brief History of the Refreshable Braille Display

Braille, introduced by Louis Braille in Paris, France in 1829, has opened up the world of reading and writing for...