From the Archive: Gender Discrimination in the Creation of the Chemistry Code

When I was working with a small collection from APH’s Editorial Department, I came across correspondence from the late 1960s that documented the creation of the braille chemistry code. This proposed code was to extend the scope of the Nemeth Code for mathematics and scientific notation, and would encompass aspects unique to chemistry, biology, and physics. Little did I know these unassuming folders would take me on such an unexpected and emotional journey that had nothing at all to do with chemistry.

The files documented the three-year project that was set to begin in 1968. Overseeing the project was APH’s braille editor, Marjorie Hooper. Hooper was internationally recognized as a braille expert and had worked at APH since 1933, rising to braille editor in 1943. The key position for this project was to be a principal investigator, who would work with a group of consultants and advisors who were experts in either braille or chemistry.

The correspondence documented the challenging process of finding a suitable candidate for the task. According to the grant proposal, without an existing braille chemical code, there were no blind chemists since “no blind person has been able to have access to texts and reference sources which would allow him to independently undertake work in this field.” So it was decided to hire a sighted chemist instead. Someone who would learn braille notation and work with the group of consultants that included Dr. Abraham Nemeth and faculty from the University of Louisville’s chemistry department.

Flipping through the documents I discovered the candidate ultimately selected was a married mother of two who had a degree in chemistry and a master’s in education. She seemed to be the ideal candidate. She was progressing along with her braille studies. But then she discovered that she was pregnant. In her letter to Hooper she said that she and her husband agreed that, if she could have six weeks off after the birth, she could continue with the project as originally planned. She conveyed how excited and committed she was to the project and how much she wished to proceed— although she left the final decision up to Hooper. However, Hooper’s reply letter stated that they couldn’t accept her offer (um, wait, what?). Hooper said that she discussed the problem with Finis Davis and Carson Nolan (both of whom later became president of APH) and they all agreed, under the circumstances, it wouldn’t be wise for her to undertake a three-year project in case she had to drop out. I was shocked.

This episode took place in 1968, a full decade before the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 which prohibits employers from firing or refusing to hire a woman for being pregnant. My 21st-century sensibilities (having only ever lived in the world of “equal opportunity employers”) were aghast at APH’s decision. I couldn’t believe she was fired in the first place, and even more so because Hooper was herself a high-ranking leader of business at a time when significantly fewer women held positions of authority. I couldn’t help but judge her through the lens of my modern perspective. And the fact that the decision was made at the institutional level made me angry.

APH’s decision ultimately allowed for another young woman (a married, full-time student and chemistry major) to have this amazing opportunity to work on the creation of a brand-new code. And by all accounts, this principal investigator did an amazing job. But that’s not the point. Had this project been undertaken today, the first candidate likely would have completed the project—or at the very least, (legally) would have been allowed to work on it. But this was a different time.

Perhaps I’ve watched too many episodes of Man Men, but the workplace for women was a very different place even just 50 years ago. What started out as me looking through a few folders that documented the creation of the chemistry code ultimately became, for me, a case study in gender discrimination in the 1960s. When I look back at how far society has come, I see all the great strides women have made. But I also see how much further we still have to go.

Mary Beth Williams is the Collections Manager at the Museum of the American Printing House for the Blind.

Share this article.

Related articles

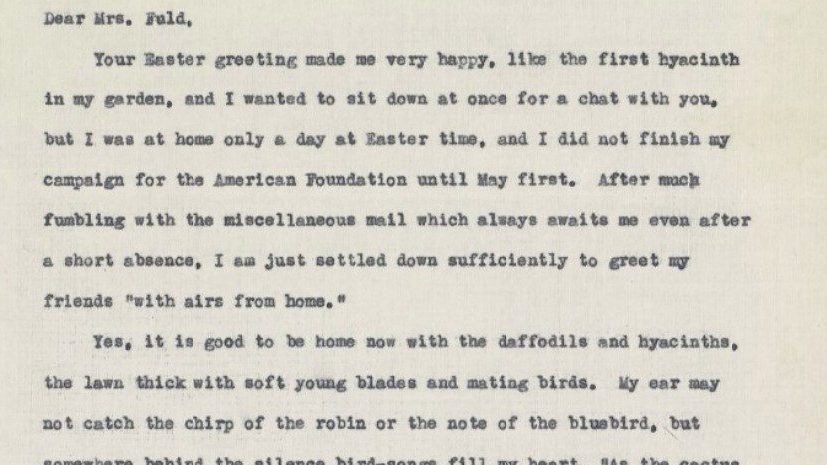

Of Beautiful Springtimes and Unfortunate Transcriptions

Yes, it is good to be home now with the daffodils and hyacinths, the lawn thick with soft young blades...

Technological Relevance in an Ever-changing World

Everything old is new again. Or so the adage goes. But there is an underlying truth to it, even if...

The Storied Life of a Time Capsule

Time capsules have long been an intriguing way for people to communicate through the ages, be they historians or grade...